Intersectionality is hot: newspapers refer to it, in academia new generations embrace it and young feminists (female and male) take pride in calling themselves ‘intersectional feminists’. But what is it exactly and how can it be of use for those of us, engaged in social change, activism and knowledge production from a feminist, anti-racist perspective? And how can we use it in Dutch academia?

In this short article I will tackle the concept of intersectionality through a set of eleven questions and answers, thus only scratching the surface of what intersectionality is all about. I’m writing this in 2015 as a Black feminist located in The Netherlands, focusing on what intersectionality could entail in a Dutch setting including Dutch academia.

1. What is intersectionality?

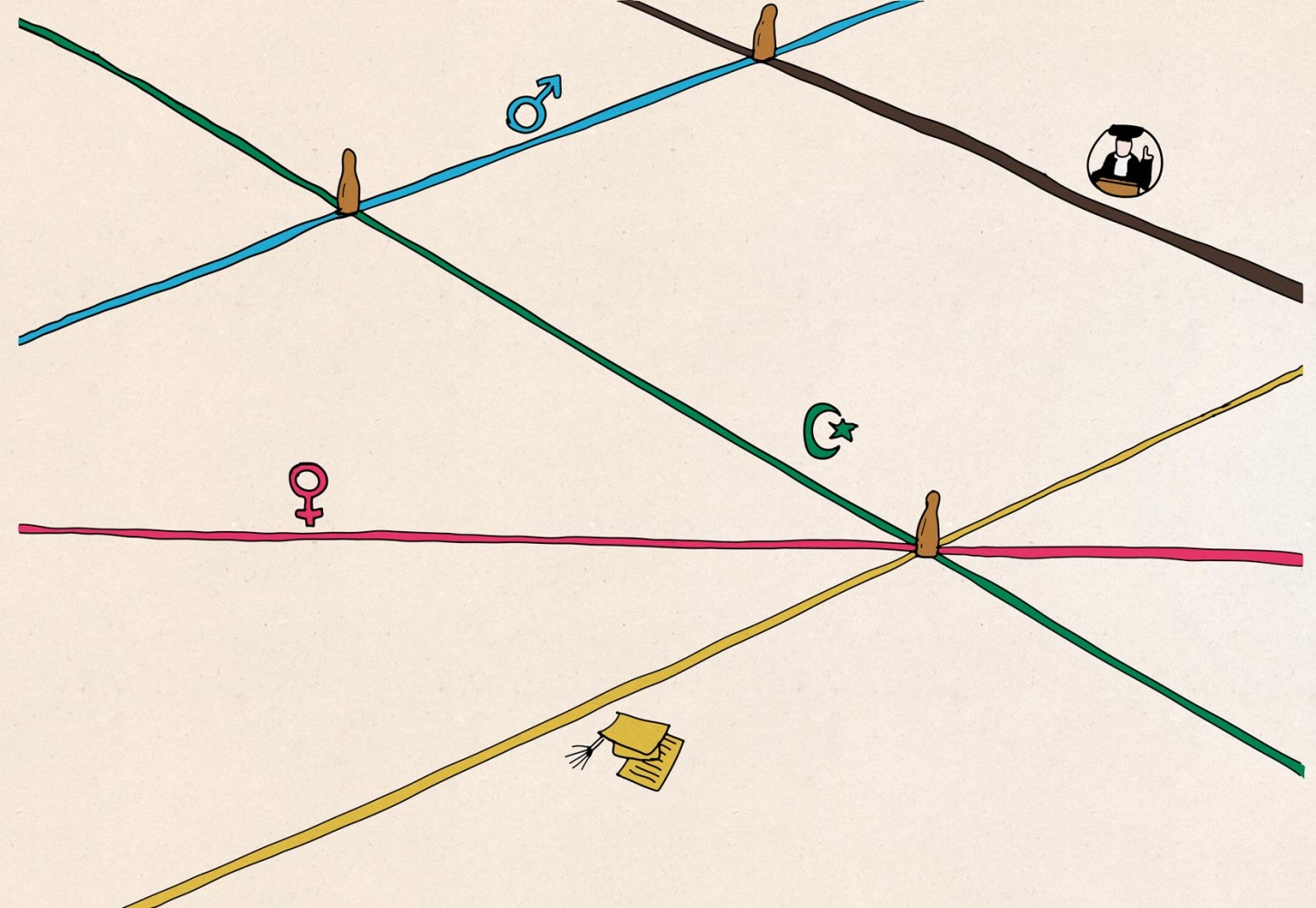

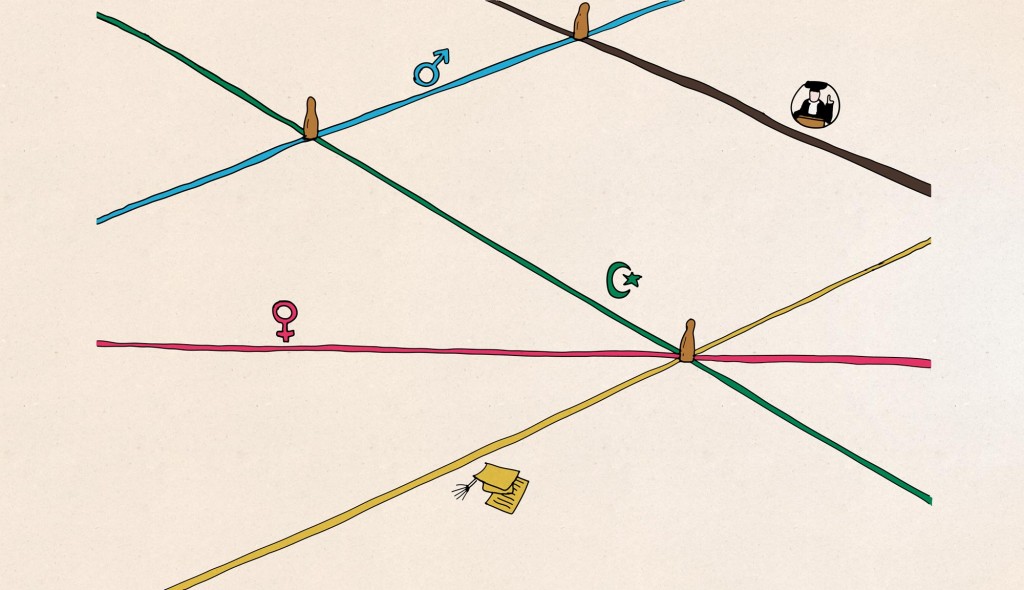

Intersectionality refers to categories of difference that we embody simultaneously (race, class, gender, sexuality, level of abledness, and so on) and how these categories interact with each other on an individual, institutional and symbolic level. The outcomes of these interactions create different power positions, which means we all inhabit different levels of privilege and discrimination.

As such, intersectionality can be useful to explain the specific forms of discrimination that for instance black queer women face but it can also uncover the specific positions of power or privilege that white heterosexual men embody. This privilege could entail a) getting a job more easily, especially top positions without competencies or biases being questioned, b) being taken seriously when speaking, or c) the assumption that they ‘belong’ in certain spaces (walking freely in a public space or gaining access to a club for instance).

2. How does it work?

First, intersectionality marks social categories of difference and shows their interconnectedness: they are interdependent and interrelated. Secondly, it points out that social categories of difference work in a way that is not cumulative but interactional, like an intersection or crossroads. Their effect runs in more than one way (for example, sexism infects and changes racism for black women, and vice versa – the sexism they encounter is in turn infected and changed by racism). Thirdly, the social categories that cross each other illustrate how one’s intersectional placement functions as an institutional privilege or barrier. Thus, intersectionality lays bare the hierarchies and power structures that exist between social categories (which doesn’t mean that these are fixed: they work in context). However, we should not forget that intersectionality is also a useful tool for empowerment.

3. Who coined the term?

Professor of Law Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality. Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) 'Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics and violence against women of color', Stanford Law Review, vol. 43, pp. 1241-1299 She wanted to address the legal and policy consequences of discrimination faced by black women. To her, it made room for specifying more finely the position of women in court cases (for instance, in lawsuits involving workers’ rights), and for pinpointing their specific positions in terms of sexual abuse and battering. In these cases, the position of white women was different from that of black women, and by using an intersectional approach Crenshaw was able to highlight that difference. Crenshaw focused on discrimination and law but since its inception the concept has broadened, both in definition and usage. Read more about intersectionality in: Kimberlé Crenshaw, Leslie McCall and Sumi Cho (2013) ‘Intersectionality: Theorizing Power, Empowering Theory’, Signs vol. 38(4)

4. In what tradition is it rooted?

Intersectionality was a lived reality before it became a term. From the 1960s/70s, Black feminist theorists and activists, notably (but not just) in the US, highlighted how mainstream feminists took the white woman as the essential norm while anti-racism thinking and activism used the black man as the norm. It meant that white women could be just ‘women’ and stand in for all women, just as black men could stand in for all blacks. Twice excluded from the norm, black women were rendered invisible, leaving little to no room for their experiences, positions and insights.

Sojourner Truth was an important abolitionist and women’s rights activist in the 19th century. Read all about Sojourner Truth, and other notable women in US history here. She had escaped slavery, having been enslaved by Dutch (she spoke Dutch as a child) and English-speaking owners in the state of New York. In 1851, a free woman, she delivered her most well-known speech in Akron, Ohio during a women’s rights convention. Her address was later re-narrated into the famous Ain’t I a woman? In her speech Truth pointed out that being black and female simultaneously was an identity that needed to be taken into account by women’s rights activists: she was criticizing the white norm that understood ‘women’ to mean ‘white women’. This was a radical insight: she deconstructed the notion of ‘woman’ by voicing the differences between kinds of women. Later on, while giving a speech in 1858, Truth was interrupted by someone who accused her of being a man. Truth opened her blouse and showed her breasts. In short: she was doing intersectionality before the term existed.

5. Can you give a Dutch example?

Ezra Coskun, a young Turkish-Dutch woman suffered brain damage after being hit by a motorcycle, becoming severely disabled. Her case was taken to court but the ruling of the judge was remarkable: Coskun was awarded only € 70,000 in damages, instead of the € 550,000 that her lawyer had proposed. The judge justified the discrepancy by taking into account the education levels of her family members, as well as her cultural background. It was understood that ”Coskun would have gotten pregnant by 26 and would only have worked part-time after that”.

Around the same time (Fall/Winter 2013) the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics noted that migrant women (especially the second generation) have full-time jobs more often than non-migrant (‘autochthonous’) women. Ezra Coskun was exactly that, a second (or third) generation migrant woman. Thus, although the facts challenged his interpretation, the judge had a reading of the case that showed cultural prejudice.

Similarly, had Coskun been a Turkish-Dutch or white Dutch man, the ruling would have been different as well because men (in both ethnicities) are seen as the primary providers for the family. The judge made a specific ruling that took into account Coskun’s gender, class, disability, and race/culture together. This ruling can only be fully comprehended by using an intersectional analysis.

6. Where is it used and by whom?

Intersectionality is used within academia, especially law, sociology, and gender studies, as an analytical and methodological tool within a curriculum (but unfortunately not as a tool to guide policy changes or discussions about diversity in academia). Second, it does guide policy development on a broader scale, for instance in the UN system (and in some cases, funding agencies). Third, it’s employed as a tool for grassroots knowledge production, organizing and empowerment. And fourth, it is incorporated into political interventions that use an intersectional lens. Intersectionality has travelled globally and influenced a deeper level of social justice awareness both in the Global South and in the West.

7. Can intersectionality be useful within Dutch academia?

Intersectionality is not used as a policy tool for academia as an institution, which still seems to struggle with diversity. Currently, ‘diversity officers’ have been installed at Leiden University (2013), the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam (2014) and the Erasmus University in Rotterdam (2015). Interestingly enough, all the officers are white women. Their installations show that new attempts are made to take diversity seriously. But only three universities have done it so far, and only very recently. As we can see, ‘diversity’ is a more commonly used term than intersectionality. It simply has not become commonplace in The Netherlands and even less so in academia.

We can wonder if academic leadership and personnel feel a sense of urgency about these issues, or have incentives that emphasize diversity, let alone intersectionality. But on a more basic level we can wonder how many people in our larger society even know and understand intersectionality. An interesting push ‘from below’ has come from The University of Colour, set up in 2015, which calls for ‘the decolonization of the University’. They are dedicated to working from an intersectional perspective and are figuring out ways to do so. This goes to show that we need more knowledge production focusing on intersectionality, connecting it to the Dutch society and academic setting, and this should be done on three levels: analytical, policymaking and practical.

8. How has it developed in The Netherlands?

The Dutch rise of Black feminism started in the late 1970s and culminated in the early 1980s. The term ‘Black’ was a political and relational term. It a) referred to solidarity among non-white women, b) engaged in a common struggle (sharing a colonial past and being victimized by racism), and c) critiqued the dominance of white, middle class, heterosexual norms of mainstream feminists. The Black women’s movement evolved into a Black Migrant Refugee women’s movement, taking into account the differences within the diverse groups of women of colour. As such, the term BMR women’s movement (ZMV vrouwenbeweging) was already an intersectional intervention.

The publication Caleidoscopische Visies (Caleidoscopic Visions) in 2001 marked 25 years of the BMR women’s movement in The Netherlands and introduced the term in The Netherlands. Maayke Botman, Nancy Jouwe en Gloria Wekker (2001), 'De zwarte, migranten- en vluchtelingen vrouwenbeweging in Nederland'. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers. It was introduced and developed by scholars like Gloria Wekker, Helma Lutz, Kathy Davis, Mieke Verloo and others. Gender Studies departments took it on board as an analytical concept, but did not produce many articles in a Dutch context, nor discussed it through regular events or publications that centralized intersectionality.

As a policy tool intersectionality became part of the government-funded organization E-Quality, which ran from 1998 until 2012 in The Hague and functioned as a group of ‘experts in gender and ethnicity.’ E-Quality was merged with other organisations into Atria, a knowledge institute on emancipation and women’s history, based in Amsterdam. Unfortunately, Atria does not seem to engage that much with intersectionality, at least not publicly.

On a grassroots level, some intercultural BMR women’s groups and lesbian networks adhered to intersectionality, but not in large numbers. An educational card game called Caleidoscopia was developed to open up discussions on diversity. All in all, intersectionality never became big in The Netherlands but is nonetheless popular in certain communities.

9. Why is it successful?

Intersectionality has been successful because it addressed a fundamental concern for feminists: the issue of difference.

By tackling multiple differences, intersectionality is more in tune with our lived experiences than any singular framework (‘I am only a woman’) could ever be.

According to Kathy Davis ‘Intersectionality as buzzword: A sociology of science perspective on what makes a feminist theory successful’, Feminist Theory, 2008, vol. 9(1), pp. 67–85 , it did so in new ways, by carving a pathway between the concerns of intersecting groups and the impacts of multiple modes of discrimination and oppression on those groups, making it a critical methodology. Furthermore, it appeals to generalists and specialists. Lastly, it has a certain ambiguousness and openness, which allows for space to discover our own blind spots and transform them into analytical resources for further critical analysis.

10. What are some of the criticisms?

Over the years, intersectionality as a concept has had its share of criticisms, such as:

- ‘It’s only about black women, only about race and gender.’ It did start there (exactly because lower class black women simultaneously inhabit multiple discriminated categories), but as we have seen in the last 25 years, it has done much more than that, and rightly so.

- ‘It’s an identitarian (focusing on ethnic/cultural identity as the central ideological principle) framework.’ Yes, it does to point to categories of difference, but it actually does so to highlight the importance of moving beyond a singular axis of thinking: beyond simply ‘women’ to ‘white women’, ‘black women’, and so on.

- ‘It’s static, it does not capture the dynamics of identity formation.’ This is a common misconception, it actually notes the dynamics at play, it does not fixate them.

- ‘It’s travelled as far as it can go and has nothing more to give.’ The current popular rise of intersectionality counters this point.

11. Where are we now?

Intersectionality looks simple, but is not simplistic. It’s difficult to understand its implications if one does not engage with it. For instance, for some social movements it has been common to use a singular framework to talk about difference and criticize discrimination (for instance only using gender, only using race), which left little space to develop further from an intersectional perspective. It is especially hard in an environment where minority groups are competing for attention. But the strength of intersectionality lies in the fact that it tackles multiple differences in relation to uneven power-relations, thus being more in tune with our lived experiences than a singular category framework (‘I am only a woman’) would.

In 2015, intersectionality seems to be entering a new phase, travelling into an era where we see a new generation of feminists, as well as a strong anti-racist movement, simultaneously on the rise. This happens both nationally and internationally and both these groups embrace (at least in part) intersectionality. It isn’t a coincidence that the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States was initiated by three queer black women.

For the first time in post-war Netherlands race issues and racism have been acknowledged as Dutch problems. This is an historical feat that was triggered by the movement against Zwarte Piet (Black Pete). These dynamic processes combined could set the stage for taking intersectionality to the next level in the Netherlands.

A longstanding institution like Dutch academia (Leiden University was founded in 1575) will probably take its time before it will use intersectionality as a tool for transformation that can uncover uneven power-relations and stimulate empowerment on the basis of difference. But however long it may take, it would be really wonderful, even necessary, for intersectionality to travel into academia and make waves.