In October of 2001, only one month after 9/11, the Associated Press published a photo of a big GBU-31 bomb, on which a U.S. Navy sailor had written, “HIGH JACK THIS FAGS.” The Gay & Lesbian Alliance (GLAAD) and the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) quickly protested against the homophobic slur (though not, unfortunately, against the creative spelling mistake of “High Jack” for “hijack”). Just as quickly, both A.P. and the U.S. Navy apologized. On Wikipedia, you'll find the entry on this little episode under the — entirely unironic — heading of “Fag Bomb.”

I open my contribution to this issue of De Omslag with this story because, to me, it perfectly illustrates how decontextualized and reductive claims of advocacy have become in the current age of identity politics. The bomb was dropped on the Afghans; yet, GLAAD and HRC jumped at the occasion as if they were its primary targets. For those two organizations, the only possible crime worth mentioning was the symbolic crime against an identity. All the rest of it — the U.S. interventions in the Middle East, the use of force, the certainty of collateral damage, in a nutshell: people dying — was apparently outside their limited area of specialization. Not their problem.

Looking back on this unfortunate chapter in the long and proud history of gay activism triggers a wry irony. For, in retrospect, it’s quite clear whose global fortunes were rising at the time (white gays), and whose were deteriorating rapidly (brown Muslims).

Identity politics is the politics based on identities rather than ideas, principles, goals, or interests. It has a long and contentious backstory: the gradual dissolution of what was once felt to be a big, happy, progressive coalition — which included various forms of socialism, movements against racism, sexism, and homophobia, and environmental and animal welfare organizations — into increasingly fragmented and specialized forms of politics. Whether or not that coalition was so happy and so inclusive to begin with remains a contested issue. If it really were, I guess, the various groups wouldn't have felt the need to split off from it in the first place.

In any event, the result has been the emergence of all kinds of single-issue and single-identity politics, which have increasingly lost not only their connections with each other, but also with the socio-economic agenda that socialism used to keep at the coalition’s center. As it turned out, certain strands of feminist and gay advocacy were only too happy to shed their troublesome socio-economic demands, and were rewarded for their assimilation into neoliberal hegemony with new rights and entitlements. If what you want is just to fit in, just to belong — without really changing all that much apart from that — then the current mode of power can and will accommodate you. Meanwhile, fundamental change has become all the more inconceivable.

Certain forms of identity politics remain entirely indispensable nonetheless. The simple fact that women don’t get equal pay for the same job as men, to name just one glaring example, makes the continuing political mobilization of the identity ‘women’ strategically necessary. That much is clear. But I also cannot quite forget that many U.S. feminists were so eager to help advance their state’s geo-political and geo-economic interests in the Middle-East with the disingenuous argument that its armies, mercenaries, drones, torturers, and companies would surely emancipate the region’s women. Similar endorsements were forthcoming from mainstream gay organizations. What made those once progressive and radical movements so easily available for opportunistic ideological co-optation?

Gayatri Spivak once captured a powerful justification of Western colonialism in Asia in a single sentence: “White men are saving brown women from brown men.” Welcome to the age of liberal imperialism, where white women are saving brown women from brown men, and white gays are saving brown gays from brown men!

To me, identity politics in the West is now the site of a volatile ambivalence. I have a very hard time trying to make up my mind. Identity politics can bring out the best in people — but also the very worst. Tragically, identity politics at present seem entirely necessary and entirely counterproductive. In the interest of the discussion, I want to detail in what follows what I find worrisome or unproductive or simply annoying about current practices of identity politics. For a possible way out, I will then address the relationship — or better the lack thereof — between ideas about “representation” or “recognition” on the one hand and “redistribution” on the other, terms that are the heart of the current political impasse.

Now that the organized call for a more diverse university has finally and belatedly reached the Netherlands in the form of The University of Colour, it’s time for us to update our assumptions about identity politics. The demands of the University of Colour can be found here. We can no longer take it for granted. It’s no longer the 1970s, nor, for that matter, the early 1990s. How has identity politics changed along the way? Moreover, according to one provocative analysis (more below), it’s precisely the West’s universities that have helped to domesticate the worldwide protest and decolonization movements of the 1960s into harmless and counterproductive forms of identity politics. How have we been complicit, and how we can prevent that from happening again? What can a genuinely critical identity politics be today?

Before I begin, two disclaimers. Though my listing of what I consider to be the less fortunate aspects of identity politics will become quite extensive, and I will probably sound needlessly sarcastic here and there, I still don’t want to suggest that identity politics is bad, that it wasn’t historically necessary or productive, or that it cannot achieve important results. I remain hopelessly conflicted on the matter, and that insecurity inflects everything to follow. If I decry the type of identity politics that was demonstrated by the two gay organizations in their response to the “Fag Bomb,” it’s from a desire for a different kind of identity politics that is less myopic and self-obsessed.

What has happened to the idea of a politics whose beneficiary is someone else rather than me and my group? That possibility is not merely passively forgotten but actively discouraged.

Furthermore, I should perhaps caution that my arguments will strike many people as overly generalizing. And that's probably the worst possible crime within the framework of identity politics — even while identity politics itself generalizes very different people under labels that are ultimately abstract. But some level of generalization is necessary and unavoidable.

Identity politics has been around for some time. It has achieved a socio-cultural life of its own, and so admits of a general shape and a general tendency — in addition to innumerable nuances and variations. There simply is a general phenomenon called “identity politics” at work in the West, which is not reducible to the sum of each and everyone’s individual intentions and positions; yet nonetheless effective. If you feel offended at any point, please consider the possibility I may not be talking about you.

Henk Krol

Let’s start with Henk Krol. Once a successful gay activist, Krol is now a member of parliament for a senior citizens’ party. Always campaigning for the underdogs, Krol is! After the revelation of the many financial scandals in which he was involved, however, I think we can safely conclude that the primary beneficiary of Kroll’s activism always was and always will be Henk Krol. He advocated for gays and lesbians, himself included. Now that he's older, he advocates for the elderly, once again himself included.

Obviously, I don’t want to imply that identity politics makes everybody as corrupt as Krol. But I do want to highlight the fact that identity politics consolidates a form of self-interest. Intellectuals and activists are expected to campaign for the group that includes themselves. Gays advocating for gays, women for women, blacks for blacks, the elderly for elderly, and so on. But if my politics is always about me, about me and my kind, that doesn’t enjoin me to open up to the suffering of others.

What has happened to the idea of a politics whose beneficiary is someone else rather than me and my group? That possibility is not merely passively forgotten but actively discouraged. Indeed, anyone who dares to speak about someone else’s plight risks being shot down for appropriation or hogging the floor.

I understand the response. There are still so many straight white middle-class men (and women) around, who earnestly believe they are able of rendering judgment on just about anything, never mind how far removed from their lived experience. But the polar opposite of that, namely forcing people to speak only of and to their own experience and identity, isn’t much of a solution either. Just because you’ve lived it, that doesn’t mean you are always right, or even that you have a compelling contribution to make. Too many discussions rapidly deteriorate into a heated fight about who has and doesn't have the right to speak on the issue.

This self-oriented focus of identity politics also tends to prevent effective cooperation between groups. Coalitions are fleeting; infighting is pervasive. Earlier, it was the feminists vs. the gays and lesbians. Today, witness the depressing spectacle of the incredibly heated fights between the emerging trans movement and old school feminists, nicknamed TERFS (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists). Each group nurses the fearful suspicion that all the others are out to water down or betray its unique claims. At times, it almost seems as if the various identities prefer to fight each other than the discrimination they suffer jointly.

The personal investment that is compelled by identity politics puts a heavy burden on individual experiences of oppression and discrimination. I don’t want to trivialize those stories. But something unproductive and potentially harmful happens as soon as those, at times traumatic, experiences are turned into intellectual and political capital, a rhetorical resource to be mobilized.

The combination of self-orientation, the validation of suffering, and the factionalism among groups leads to one of the nastiest aspects of identity politics — comparative suffering, the rivalry over who is hurting the most.

Identity politics validates itself through pain and anger; it’s therefore not always the right context for people to learn how to deal with their sorrow in helpful ways. It's not a good idea to expect, even allow, people to authenticate themselves politically and intellectually on the basis of their hurt. Sometimes students feel subtly obliged to perform and reiterate scenes of woundedness, vulnerability, and grievance. According to Jack Halberstam, a big name in queer and trans studies, this can easily lead to a generalized “culture of umbrage," in which people feel perpetually injured and offended by each other. See Halberstam's blogpost “You Are Triggering Me! The Neo-Liberal Rhetoric of Harm, Danger and Trauma.”

Halberstam goes on to denounce the general imposition of a vulnerable self-image, a sense of self so fragile it is instantly shattered by micro-aggressions or symbolic triggers. It is in this context that organizations like The University of Colour call for a university that would be “safe” and “comfortable” for everyone. Obviously, harassment and abuse should have no place at a university. Nevertheless, there’s only one place on this planet that’s truly safe and comfortable for everyone, and that’s Disneyworld. The request for safety and comfort can easily be turned against imaginative, critical, and provocative works of art and literature. It’s simply not possible to study the legacies of racism and homophobia, moreover, without exposing yourself to racist and homophobic material. The demand for a perfectly safe environment dubiously coincides with the promises of the security, surveillance, and “nanny” state. Are we sure we want the government and governmental entities, like public universities, to have even more powers to protect us from each other and ourselves, for our own good?

I wish for an identity politics less obsessed with measuring and dividing up quantities of suffering.

The combination of self-orientation, the validation of suffering, and the factionalism among groups leads to one of the nastiest aspects of identity politics — comparative suffering, the rivalry over who is hurting the most. One acute example of this fixation comes from a canonical essay by the critic Leo Bersani. "While it would of course be obscene to claim that the comfortable life of a successful gay white businessman or doctor is as oppressed as that of a poverty-stricken black mother in one of our ghettoes ...," Bersani begins — and then goes on to claim precisely that and more. Bersani, Leo. “Is the Rectum a Grave?” October, Vol. 43, AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism, Winter, 1987), pp. 179-222. Successful white gays are not just as oppressed as poverty-stricken blacks, they are actually more oppressed. Gays, he claims, are considered a "disposable constituency" in a way that African Americans are not.

Granted, the essay was published at the height of the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, when it became clear that the American political establishment couldn't care less that so many gay men died. Yet, as the excesses of Hurricane Katrina, the prison system, the War on Drugs, and police violence have demonstrated since, that same establishment doesn't care much about black deaths either.

As I write this, I realize I have fallen into the trap of comparing histories that should not be compared to begin with. The comparison equates fundamentally different histories by introducing a common denominator; here, cynically, the number of deaths. The tendency to calculate and equate qualitatively different historical experiences makes some forms of identity politics self-defeating at best, malicious at worst. I do wish for an identity politics less obsessed with measuring and dividing up quantities of suffering.

Halberstam’s daring complaint about a “culture of umbrage” brings me to the extremely limited scale of emotions that tends to accompany identity politics in its current form. In principle, all kinds of emotions can inform political engagement: from joy to boredom to care to laughter. But for identity politics, it's nearly always the same mixture of earnest sentimentality, righteous indignation, and outrage. Stemming from American puritanism, those affects have nearly monopolized the field. Anything less than complete seriousness is already something of an infraction. But how effective can any form of politics be if it depends on such a stifled range of emotions?

Could it be that the furious conflicts about symbols have started to serve as a diversion from, not a facilitator of, genuine social change?

Of course, the deadly seriousness of identity politics also characterizes its perspective on language and imagery. GLAAD and HRC went so far as to take the symbolic slight of the word "fags" more seriously than the physical damage of the bomb. They also chose to overlook the fact that the term of abuse was actually addressed to Muslims, not to American gays. Blatant expressions of racism, homophobia, transphobia, and sexism should surely be condemned. But that doesn't mean we have to be so exceedingly literal-minded about words and images; symbols may well be layered, ironic, twisted, complex, ambivalent. I am not so sure many minorities will ultimately be better off in a world that would censure all verbal and visual play, experimentation, and trickery; a world where every word only means what it means.

For a long time, I believed that the disputes about representation and language would help raise awareness, so that real change would follow. Now I'm no longer sure. Since the politicization of terms and images is so much more advanced and more accepted in the U.S. than it is in the Netherlands, one would expect that American society would therefore also be manifestly more just in its real-life treatment of minorities. That doesn't appear to be the case at all. For one thing, the U.S. Justice system remains blatantly racist against the poor.

Could it be, then, that there is ultimately not such a big connection between representational identity politics and material circumstances? And even worse, could it be that the furious conflicts about symbols have started to serve as a diversion from, not a facilitator of, genuine social change?

Diversity Management

One beneficial result of identity politics, it is often claimed, is a widespread affirmation of diversity and difference. That apparent achievement, however, has suspiciously coincided with the switch of global capitalism from a business model based on mass production and consumption to an investment in cultural variety. A brand like Coca-Cola, for instance, has long evoked a bright image of global diversity that is entirely conditional on its product: we can all be different as long as we all buy Coca-Cola. In a similar vein, many Western companies have deployed forms of diversity management that are facilitated by rigid HRM protocols. Conspicuous celebrations of diversity and hybridity frequently conceal implicit regimes of homogenization.

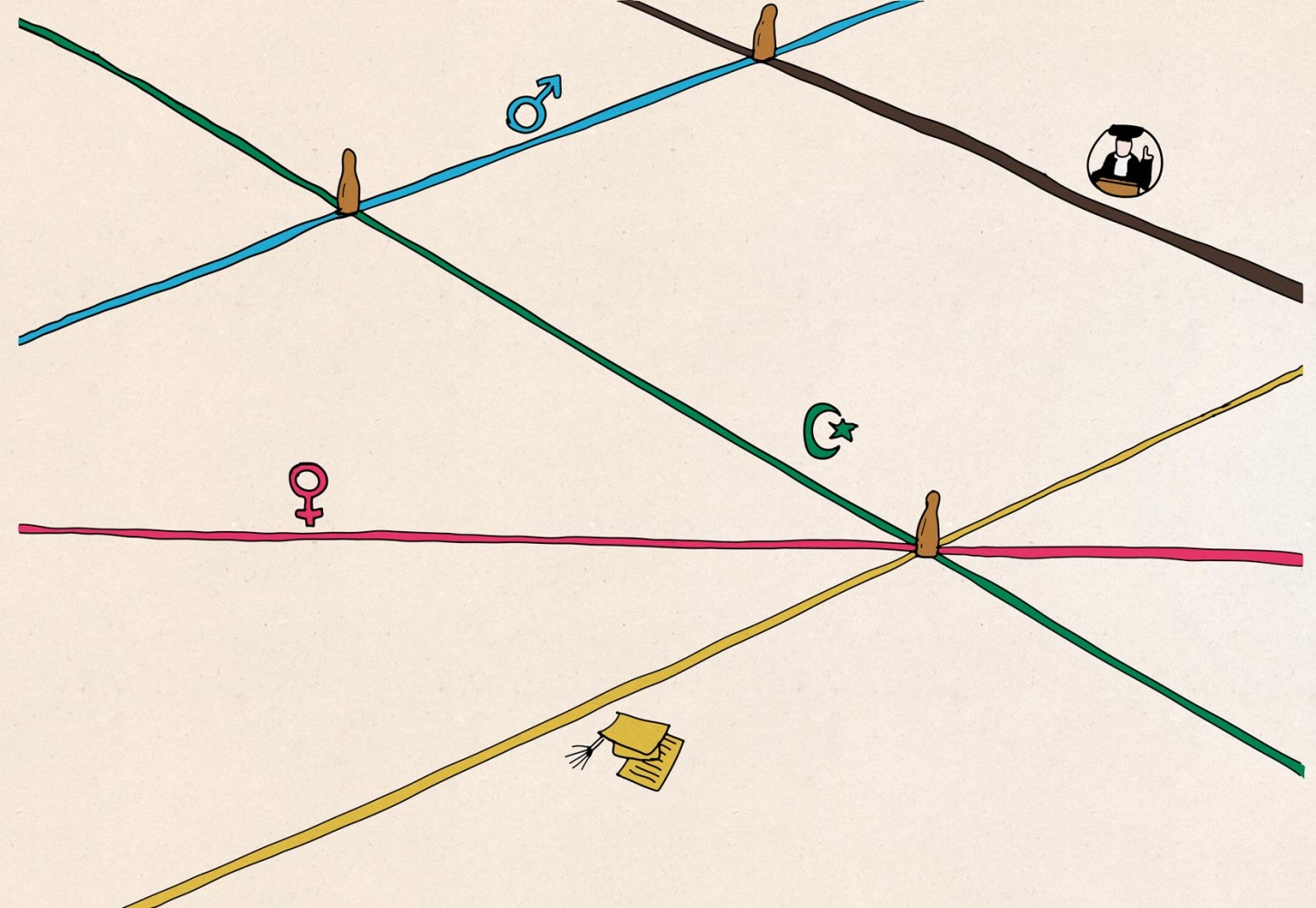

Activists and intellectuals have their own way of flattening out diversity. In a pervasive habit of thought, different historical identities are related to each other on the basis of a minimal logic of normative self and other. This is often done in the spirit of solidarity, but the result is the opposite. For, if black stands to white as gay stands to straight, then black equals gay and white equals straight. But being gay is not a different way of being black, or vice versa.

Western companies have deployed forms of diversity management that are facilitated by rigid HRM protocols. Conspicuous celebrations of diversity and hybridity all too frequently conceal implicit regimes of homogenization.

The attempt to relate identities ends up equating them, neutralizing entirely different histories and socio-economic constellations. This way of thinking underlies Bersani's obscene “comparison” between a successful gay white businessman and a black woman living in a ghetto. Appeals to a generalized or common diversity turn out to negate difference. No difference makes a real difference anymore, because all differences amount to more of the same.

The term "intersectionality" was introduced by black feminism to account for the simultaneity of layers of injustice. The notion remains contested. Some academic work on intersectionality is criticized for similarly neutralizing difference, merely adding up multiple identities into a generalized diversity. Indeed, intersectionality means little if it doesn't open out to global class relations and planetary welfare. That perspective is especially urgent now that Western states, NGOs, and multinationals aggressively export identity and diversity politics across the globe. The assumption is that Western categories of race, gender, and sexuality unproblematically translate to all contexts so that their imposition would invariably be beneficial.

It's an understatement of colossal proportions to point out that the colonial archive doesn't support the good intentions of Western pedagogies — especially when they sound “enlightened.” Non-western cultures have their own sophisticated ways of accommodating differences between people. Sometimes these allow for less freedom, sometimes for more, but in all cases the balance is not easily called by ignorant outsiders intent on doing good. The brutal imposition of Western categories and scripts can make matters far worse.

No difference makes a real difference anymore, because all differences amount to more of the same.

Fortunately, not all minorities everywhere are eager to accept the West's heavy-handed patronage. When Obama protested Putin's anti-gay law — while several American states have similar or worse laws on the books — one queer group in Russia brilliantly responded: we are against Putin; we don't need Obama to speak for us; we don't like the sexualized and commercialized homosexuality of the West; thanks but no thanks.

Incidentally, who thinks it's a smart idea for states to advocate on behalf of each other's minorities should perhaps think back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Then, nations jockeyed for power and territory by leveraging ethnic minority rights over each other. It didn't end well. In a similar way, contemporary identity politics is becoming part of the West's global power play, just another form of "soft power" to help legitimize military and economic violence.

Distributing Identity

So, should we conclude that identity politics has outlived its viability, the bad now overwhelmingly outweighing the good? Thought-provoking contributions to this debate have been offered by Nancy Fraser and Roderick A. Ferguson. Fraser comes from Philosophy and Women's Studies; Ferguson's specializations are in Sociology and African-American Studies; read them together, and they can help bring the current impasse of identity politics into sharp relief.

Fraser proposes what seems to be a clear and helpful set of distinctions. Fraser, Nancy. “From Redistribution to Recognition? Dilemmas of Justice in a ‘Post-Socialist’ Age.” New Left Review (1995), pp. 68-86. On the one hand, there are groups of people, like the traditional working class, who suffer from economic exploitation. The justice they require entails a redistribution of wealth. On the other hand, there are also people, lesbians and gays, for example, who suffer from cultural forms of discrimination. The justice they seek entails the recognition of their identity. A third type of groups, which includes women and blacks, cannot be situated on either end of the scale. Doing them justice would require the combination of material redistribution and symbolic validation.

Many times, Fraser repeats that her distinctions and examples are only meant analytically, heuristically. In the real world, economic and cultural inequities tend to go hand in hand, so that justice usually requires both redistribution and recognition. However, since she only ever mentions the two specific examples to flesh out her distinction — the working class and gays and lesbians respectively — they become more than just examples. The two groups come to epitomize pure or ideal opposites: working class-exploitation-redistribution versus gays and lesbians-discrimination-recognition.

“Identity” is not what people are; it is a political strategy.

That picture isn't historically accurate. The fight for sexual emancipation was also about the redistribution of access to legal protection, jobs, health care, privacy, adoption, inheritances, and so on. Fraser's model only describes the gay and lesbian movement after its co-optation by neoliberalism; after the movement had shed its ties to the larger and solidary coalition of the Left, when sexual freedom was still intimately related to other causes and identities. Fraser's distinction only seems so clear because it mirrors and repeats the status quo. The distinction turns a historical event into philosophy and so ends up implicitly endorsing a neoliberal identity politics.

Precisely on the basis of Fraser's argument, I want to propose two different conclusions. All political identities, not just those of gender and race, are what she calls “bivalent,” situated in the middle. People start mobilizing an identity when they suffer from exploitation-discrimination to help them to fight for redistribution-recognition. The two sides are always intersectional, and so they should be. “Identity” is not what people are; it is a political strategy.

That also means that no identity is forever. For Fraser, a key difference between the working class and gays and lesbians is the ontological status of their respective identities. If the working class achieves its political goal and is no longer exploited, then it's no longer the working class, so it instantly stops existing as such. However, when gays and lesbians are validated and no longer discriminated against, their identity doesn't go away but remains in place. For Fraser, sexual identity is “chronic” in a way that class isn’t.

The question whether exploitation and discrimination can and should be distinguished is so crucial because their dissociation is at the heart of the current formation of power

But there is no reason to assume that sexual identities wouldn't dissolve or become depoliticized if full justice were to be reached. In a world of perfect equality, how functional would sexual labels still be? No more than the difference between those who like their popcorn salty or sweet. Now that's surely a paramount distinction — though not necessarily a politically relevant one. Sexual identities don't necessarily need to be more “identitarian” than class.

The question whether exploitation and discrimination can and should be distinguished is so crucial because, according to Ferguson, Ferguson, Roderick A. The Reorder of Things: The University and Its Pedagogies of Minority Difference. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012. their dissociation is at the very heart of the current formation of power. In response to the strong protest and decolonization movements of the 1950s and 1960s, he argues, a new compromise emerged between power and its contestation. That compromise rested on the separation between redistribution and representation (or, in Fraser's terms, recognition). In a bait-and-switch move, the limited equality promised by a more diverse regime of representation was generalized at the cost of socio-economic redistribution. Hence, the supposedly neutral distinction that Fraser proposes actually describes a shrewd real-world dissociation that enabled the co-optation of a serious challenge to power.

In that way, the protest and decolonization movements were neutralized in the interests of global capital. Worse, Ferguson claims, a tamed progressive politics celebrating diversity ended up actively supporting capitalism in its commodification of global cultural variety. Precisely as the world became more and more unequal economically, activists and intellectuals focused nearly exclusively on matters of representation, identity, and difference.

Where was that compromise enacted? At Western universities, Ferguson claims. Through what he calls “pedagogies of minority difference," universities trained people to prefer representation over redistribution. Representation in the double sense of the inclusion of minorities in canons, course syllabi, programs, and faculties, as well as of academic criticism of symbols: images, stereotypes, slurs, hate speech. Indeed: fags rather than bombs. We have been complicit.

We are a statistic

I disagree with how Fraser makes lesbians and gays carry the burden of a bad identity politics. But I agree with the thrust of her conclusions and recommendations. Redistribution, either upward or downward, is the true goal of all politics. For the Left, the object is the more equitable sharing of access to knowledge, power, and wealth.

Identity politics can certainly help with that — but it can also hinder. It helps if identities remain provisional strategies in the service of more socio-economic justice for everyone. It starts to hinder when, decontextualized and reified, those identities proceed to promote self-interest exclusively. The goal of a productive identity politics is not to leverage the claims of one group over everyone else, but to dissolve, becoming unnecessary, in a society that is more just for everyone, not just for the one or the other group.

Of course, such forms of identity politics never went away completely, even if they seemed at times to be drowned out by the pushy assertions of their neoliberal counterparts, especially in the feminist and gay movements. At the worldwide Occupy events in 2011 and 2012, all the usual identity groups and social justice warriors were present and accounted for. Nonetheless, the central slogan was, “We are the 99%.” The slogan foregrounded an “identity” that wasn’t an identity at all but a statistic — nothing more than a number indicating a socio-economic class that is now nearly all-inclusive.

In today’s generalization of identity politics, however, each productive step is speedily countered. Consider the phenomenon of “wealth therapy,” counselling for the 1%. You see, the 1% constitutes another oppressed minority. In a report in The Guardian, one therapist explains, “It’s an -ism. I am not necessarily comparing it to what people of color have to go through, … but it really is making value judgments about a particular group of people as a whole.” Another therapist adds, “Sometimes I am shocked by things that people say. If you substitute in the word Jewish or black, you would never say something like that.” The media are to blame for “making the rich ‘feel like they need to hide or feel ashamed.’” I guess it’s safe to conclude that justice for the 1% would rather require the recognition and validation of their identity than an effective form of wealth redistribution.

Apparently, it is now entirely possible to mobilize the discourse of identity politics, not just in the absence of any concern for global material justice, but in active psychological support of extreme inequality. Identity politics can no longer be trusted. It’s time to criticize and reinvent it.